sHOP STORM 36

Nicolas Sassoon came of age during an influx of computerization and accelerating technology. A new era when humans began to pass time in the dim glow of personal computers and video game consoles like the Atari 2600 and Amstrad CPC. Growing up in the 80s and 90s, he was unaware of the impact these novel, visual experiences would have on him after the turn of the century.

As a young man, Sassoon studied art in Angoulême, France. He learned to paint and draw. He focused on sculpture and installations. Eventually he earned his Master’s. In 2008, he looked to start anew in a foreign country, no longer confined by the pressures of academics. All the while, thin memories of 8-bit graphics and pixelated visuals sat dormant in his mind. Following his migration to the Pacific Northwest, he would be free to create based on instinct and urge.

Today, Sassoon is fixated on early computer imaging techniques. Utilizing rudimentary imaging software and his intricate language of abstraction, he creates hypnotic digital animations indicative of the early computer graphics from the days of his youth.

Digital renderings of our surroundings—meteorological conditions, environmental landscapes, manmade structures—are developed through a conscientious method of pixilation and experimentation. Sassoon’s origins in the traditional arts ingrained in him a uniquely analog perspective, and his process is more handmade than automated; a distinction worth noting in a world of digital perfection, where the need for human touch diminishes exponentially.

Sassoon’s intent is to translate a sense of nostalgia into an entirely new experience. He focuses on familiar visual cues and proceeds to isolate, distort, enhance and push them into new optical territory. The result is a range of mesmeric works that imitate the natural world and produce a new visual experience. Every project is created—and consumed—through the intimate relationship that exists between user and computer.

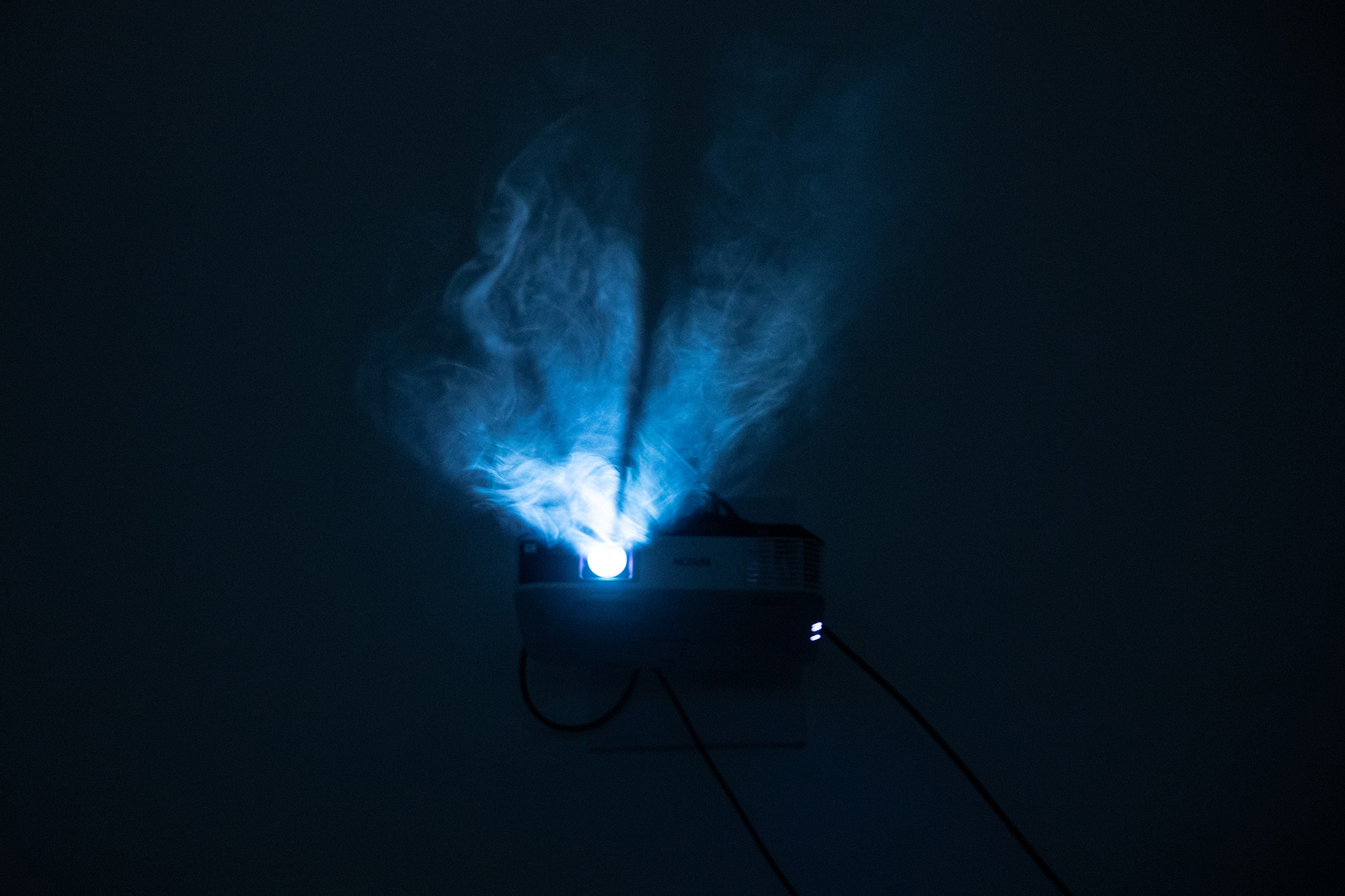

The recurring intersection of the natural world and technology permeating Sassoon’s work is at the foundation of “Storm 36,” a digital rendering of Vancouver’s inclement weather and the focal point of his partnership with wings+horns.

Storm 36 utilizes a moiré technique, overlapping two images to create the illusion of a third. Elements of constant motion amplify the effect and produce a trance-like sensation. Deceptively asymmetrical and incomplete, the screen-based sequence endlessly repeats, resorbing into itself, taking the viewer with it.

Sassoon’s Storm 36 is a reflection of his experience in Vancouver. A decade of heavy winter weather and the outside world, as he observed it, through a single window in his studio—the rain creating patterns on a pane of glass, fixed in a loop, over and over. The collaboration features a freeze-frame of the digital animation. Storm 36, our natural world and the technology within it, to be observed in a newly altered state; a single moment in time.

“My work is really inspired by landscape and natural forces in general. I think the Pacific Northwest is a really good place to experience these kinds of things. You can experience natural forces in a very extreme way. A lot of my abstract work stems from that experience of landscape and natural forces, and I strive to translate those experiences, which are physical experiences, into an abstract, digital experience.”

“Every time you look north you see the mountains, and it’s a reminder that wilderness and nature are very close. It’s a perspective I can escape to — I can look in one direction and I can see that in this direction there is no more city. It is wilderness, and that’s something that feels grounding to my experience.”

“Storm 36 is one of the works that is most relevant to my experience of the weather in Vancouver. It really speaks to this experience of winter, this experience of dark days that are really wet and rainy. It’s an experience that has been really heavy over the years. The animation, and this whole series, was in some ways cathartic because it allowed me to take something that used to feel very heavy and turn it into a project, something exciting, not something that felt passive.”

“I find it a sort of reassurance, the idea of dedicating my entire life to a specific way of making images. Technology is everywhere around us and it creates this disruption in our everyday life. It creates this new rhythm, it creates this new environment, and this sort of speed as well. I find developing your type of craft within that environment is also a way of regaining control over it. It creates a grounding experience where I can finally connect my experience of computer technology with my experience of daily life.”

“With early computer graphics there’s an inherent relationship with patterns and embroidery because when you look at the early computer graphics, you see pixelated patterns that are reminiscent of textile patterns. Developers who created certain types of pixel patterns looked at textiles and pieces of clothing and fabrics to create them.

There is a strong relationship with pixelated patterns and the patterns you find on physical forms, on fabric and on clothing. It’s a natural cycle for a digital work like mine, which uses heavily pixelated patterns, to end up on a piece of fabric, because it speaks to its own origins and the history of textiles, the history of weaving, the history of embroidery—it’s a sort of way to loop the cycle.”